Strand Consult has covered global net neutrality policy for almost two decades and has performed empirical research and assessment on the different instruments of the policy and associated outcomes. Strand Consult’s library contains dozens of reports and research notes on the topic with case studies from around the world.

RELATED: Next chapter of net neutrality wars in US, rest of the world – Strand Consult

This note covers the recent ruling in the Sixth Circuit in a case brought by broadband providers against the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), a status update on the European Union (EU), how Big Tech has used the policy to win regulatory advantage, and takeaways for the rest of the world.

Separately, Strand Consult’s EVP Roslyn Layton, PhD submitted a pro-bono amicus brief in favor of petitioners in the Sixth Circuit. In 2018, she submitted a pro-bono brief in favor of the Federal Communications Commission and its Restoring Internet Freedom Order.

Court: The FCC’s flip-flopping ends now

A unanimous decision of 3 judges in the US Sixth Circuit struck down the Biden FCC’s Safeguarding and Securing the Open Internet Order. This decision represents the FCC’s 9th flip on the policy. Circuit Judge Richard Allen Griffin declared, “Applying Loper Bright means we can end the FCC’s vacillations,” referring to recent Supreme Court ruling that regulatory agencies must respect a plain reading of statute and not over-interpret the law to suit their policy whims.

The court affirmed Congress’ intent that the internet be only lightly regulated and thus rejected the FCC’s latest attempt to impose so-called net neutrality rules. Importantly the court found that broadband is an “information service” under the Communications Act and hence the FCC cannot regulate it as if it were a “telecommunications service”.

FCC cannot regulate “mobile broadband” as a commercial mobile service

Moreover, the court found that the FCC cannot regulate “mobile broadband” as a commercial mobile service. These may seem arcane points, but they have critical legal meaning. To put it in other words, the Communications Act has a series of buckets in which Congress assigned different services with different levels of regulation.

The FCC rules attempted to change the services within these buckets to suit its purposes. The court says no go; the FCC does not get to rewrite the law. Regulators can only regulate that which they are authorized to regulate.

Big Tech, a key driver and beneficiary of net neutrality, has lobbied to make broadband networks “dumb pipes.” It wants broadband classified in the “telecommunications” bucket so the FCC can regulate broadband providers like “common carriers”, controlling broadband prices and practices.

Big Tech wants the FCC to keep broadband prices low so that consumers spend more on Big Tech services; moreover, Big Tech wants the FCC to force broadband providers to overbuild networks to accommodate growing Big Tech traffic rather than allow broadband providers to use pricing and technology to manage traffic flow efficiently.

Court explores whether broadband is “telecommunications service”

The court’s decision explored the question of whether broadband is “telecommunications service” under US law. It considered whether broadband is mere “transmission” of data (sending data between points specified by the user without change in the form or content of the information as sent and received) like a telephone call.

It rejected the view that broadband is “transmission” of data. Instead, the court found that broadband satisfies the legal concept of “information service” in which data is acquired, stored, and utilized and whose providers cannot be classified as common carriers per US law. As broadband is clearly in the “information service” category, the FCC’s re-categorization and subsequent regulation are illegal.

Importantly the court censured the FCC for omitting a key element of the law in FCC rules. The broadband provider need not itself generate, process, retrieve, or otherwise manipulate information to provide an information service. Rather, the provider need only offer the “capability” of an “information service. This may seem like a small point, but the judges caught the FCC in evading the law.

The 2015 FCC invented a new name for broadband providers calling them “Broadband Internet Access Providers” (BIAS). It appears this was an FCC gambit to portray broadband providers as merely providing access to information services but not being an information service providers themselves. The court rejected that sleight of hand.

No “net neutrality” or its equivalent in the Communications Act

Tim Wu, who coined the term net neutrality, called the decision “judicial activism”, the view that courts can and should go beyond the actual law to achieve preferred political goals. The judges read the law and found no authority for the FCC to regulate broadband. The fact remains there is no term “net neutrality” or its equivalent in the Communications Act. Congress has not instructed the FCC to regulate broadband as such.

Rather, the court reiterated what Congress asserts: the policy of the United States is “to preserve the vibrant and competitive free market that presently exists for the Internet and other interactive computer services, unfettered by Federal or State regulation.”

It seems that California and New York ignore Congress’ intent when it comes to an internet “unfettered by State regulation.” It is presumed that a federal policy of deregulation preempts the states from imposing the same or similar rules at the provincial level. However, both red and blue states have sought to regulate different aspects of the internet in conflict with federal law.

FCC’s flip-flopping as business model for the telecom bar

The FCC’s flip-flopping became a business model for the telecom bar. The Sixth Circuit decision is directed to some 50 law firms or advocacy entities engaged in the litigation over the FCC’s net neutrality rules. These two decades have generated hundreds of millions of dollars in billings for law firms, to say nothing of the political fundraising efforts by advocacy organizations campaigning to “save the internet”.

Congress has tried to make a net neutrality law, but it’s not popular with voters. The emergence of 5G essentially mooted the issue. Americans today consume more internet data per capita than any nation. In 2018, there were some 3 million public comments to the FCC for and against the rules’ repeal. In 2024, the FCC received but 50,000 comments in response to its rulemaking.

EU’s internet sector worse off after a decade of net neutrality

Compared to the flip-flopping in USA and relative light to touch to broadband until 2015, the EU has imposed hard net neutrality rules on the European telecom sector for a decade. They did this with a law in the Parliament promulgating that such rules were needed “guarantee the continued functioning of the internet ecosystem as an engine of innovation.” EU policymakers celebrated the law, and indeed, they should be judged on whether the policy worked to foster the promised internet innovation in EU. The data points in the opposite direction, however.

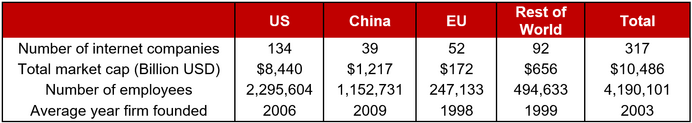

In 2025, the EU trails the US and China in internet startups when measured by the number of publicly traded firms, market capitalization, and year founded. The EU remains a one hit wonder of the internet. Sweden’s Spotify accounts for more than half of the total EU market capitalization. Ironically the very strategy that allowed Spotify to get a foothold in the market–partnerships with EU telecom operators which marketed premium Spotify subscriptions–are illegal in the EU today because of net neutrality rules.

One other exception is Booking.com, founded by a Dutchman in 1995, which was acquired by the US-based Priceline in 2005. The EU startups that do exist are largely mobile apps. There are essentially no top-ranked, EU-based firms in consequential fields like operating systems, search, social, cloud, ecommerce, or AI. The following table summarizes the information for the top 317 global internet firms in US, China, EU, and the rest of the world.

Net neutrality and EU internet firms

EU based internet companies account for just 2 percent of the world’s total internet market value, just 52 firms, and less than 250,000 workers. The average year of founding is 1999, showing that little to no EU internet firms have been founded since 2015 when the net neutrality rules were imposed. By contrast, the US and China continue to mint new internet companies, for example Trump Media founded in 2021 has $7.5 billion market cap, an amount larger than all but 3 EU internet companies.

The loss of broadband network investment has accelerated in the EU since 2015, and today the region faces a gap as large as €200 billion by some measures. Austrian economist Wolfgang Briglauer has performed the definitive studies on net neutrality’s impact to wireline and wireless networks in more than 30 OECD countries over two decades, showing conclusively that net neutrality rules deter investment in broadband networks. The econometrics delineates what is intuitive: regulation which reduces the network owner’s ability to price and manage traffic reduces the value of the network.

EU and US broadband investment

The light touch approach to broadband has proved superior in the USA. Indeed, while investment dipped following the imposition of the FCC’s 2015 rules, it came back following the restoration of a light touch approach in 2018. Not only do broadband providers continue to invest in networks in USA, the gap increasingly widens compared to Europe, with the US investing on average three times more per capita than European broadband firms.

The European Commission houses the annual reports from national telecom authorities which collect data on their net neutrality implementation, offering a testament to regulatory busywork. Each year European regulators congratulate themselves on the compilation of these reports, which amounts to a chronicling of disincentives to the digital sector. Ironically each new European Commission decries the lack of internet innovation by EU firms, but it refuses to examine its own mistakes and failed policies, namely overregulation of the telecom sector and rejection of consolidation. Sadly Strand Consult expects more of the same from EU.

Net neutrality is not the global standard

For some years, Big Tech used FCC policy to justify its policy efforts (see Strand Consult’s coverage of Netflix litigation in South Korea and Meta in Germany), claiming that net neutrality is the global standard. The Sixth Circuit decision disproves that argument, striking down US rules.

The EU’s approach to broadband is not working to serve consumers, innovators, or investors, and the region is an also-ran for internet startups. Strand Consult documented this in its 2022 report “Net Neutrality regulation is failing UK consumers, innovators, and investors.

It’s time for broadband internet policy that improves consumer welfare, internet innovation, and network investment for the UK” showing that upon leaving the EU, Ofcom in the United Kingdom determined that the EU’s excessive regulation deterred valuable innovation in consumer broadband markets and 5G investment.

Freedom for broadband providers to provide free data

Subsequently, Ofcom restored freedom for broadband providers to provide free data and network management. Switzerland also diverges from the EU on net neutrality. Significantly Australia and New Zealand have never imposed net neutrality rules. South Korea and Japan have light touch regimes based on guidelines.

Recently Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina have reduced or removed telecom regulatory authorities, finding that telecom policy can be more effectively implemented through competition authorities and/or other business ministries. Already in 2014, Denmark determined that it needed no standalone agency for telecommunications and dismantled the traditional regulator, repurposing resources to cybersecurity efforts.

Indeed, this follows the ideal type of regulation: once the goal is achieved (for example the privatization of the national telephone monopoly), the regulatory agency should be wound down and the resources returned to the people. The emergence of net neutrality in 2003 disrupted this normal process and created new constituencies for regulatory agencies which otherwise were obsolete. Big Tech thus acquired net neutrality, and telecom regulators operate it for Big Tech’s benefit.

The purpose of net neutrality is to protect Big Tech and subvert competition

Net neutrality promoters Tim Wu, Larry Lessig, Barbara van Schewick and others have been affiliated with organizations, institutions, and universities which received significant funding from Google (see extensive coverage from Wall Street Journal), for example the Stanford Center for Internet and Society which was supported by Google to promote policy concepts like net neutrality, open access, and the re-interpretation of fair use and copyright to serve Google’s business objectives.

The strategy is to reduce the property rights of owners of telecom networks, content, and relevant patents, so that Google (and other Big Tech platforms) can use them for free or at a reduced rate. The policy strategy has greatly enriched Google and other platforms. Strand Consult explains these actors and their tactics in its report “Understanding Net Neutrality and Stakeholders’ Arguments.”

Big Tech lobbying for net neutrality

]Big Tech, through its trade associations and individual companies, lobbies for net neutrality and funds many academics, think tanks, and civil society organizations to advocate for it. Relatedly foundations like Ford, Open Society, Mozilla, Knight, and others with significant holdings of Big Tech stocks have funded net neutrality advocacy. Strand Consult described the global net neutrality advocacy and coalition in its report on Big Tech’s transnational advocacy, “Follow the money – Net Neutrality Activism Around the Globe.”

Big Tech entities realized early on that eliminating pricing differentiation for data was essential for their business models. Hence it perpetuated the net neutrality myth that all data is equal. Specifically, net neutrality harms consumers by forcing them to value all data equally.

Under net neutrality consumers must pay for advertising traffic the same as they pay for the data they actually want. Today advertising consumes 25 percent of all traffic and is growing. As much as 80 percent of all internet traffic comes from just a handful of Big Tech firms. Neither consumers nor broadband providers can control this traffic. Big Tech always sends more traffic into networks, and they don’t want to pay for it. The point of net neutrality is to ensure that others bear this cost.

Some foolishly believed that net neutrality would create the next Google. If that was the case, such a firm should have emerged in Europe or India where rules are the toughest. Precisely the opposite has happened. Indeed, Big Tech has the biggest market share where net neutrality rules are in place. Any upstart which wants to use a different technology or pricing strategy is not allowed because of net neutrality.

Bottom Line: Laws are made by legislatures, not regulators. It’s time to repeal laws that harm consumers

If net neutrality rules are extant in your country, they are likely harming consumers, innovators, and investors and should be modernized. Unsurprisingly Big Tech and its cronies have attempted to conflate issues like fair share and net neutrality; after all, “net neutrality” is their empty vessel for the policy issue du jour. They cover up digital colonialism with net neutrality. Strand Consult documents Big Tech’s digital colonialism in the Caribbean in its research note “The Caribbean is a microcosm of Big Tech’s digital colonialism. Small and medium-sized emerging countries are profitable to exploit” and related report “Gigabit Caribbean: Closing the Investment Gap in Fixed and Mobile Networks.”

However, in point of fact, where net neutrality rules and laws have been promulgated, they apply specifically to the consumer side of the market, the relationship between the end user and the broadband provider. Fair share is about the business-to-business side of the market, the relationship between the broadband provider and Big Tech. Broadband is a two-sided market, with a different set of services provided to each side: Consumers receive connectivity, access equipment and technology, and account management. Big Tech receives access to the broadband provider’s subscribers, hosting/processing, security, and other services.

Fair share and broadband cost recovery solutions will expand the availability of networks for end users because Big Tech takes on a share of the burden, versus the status quo of Big Tech’s free ride. Hence financial contributions from Big Tech for network deployment and end user affordability are absolutely consistent, if not essential, for internet inclusivity.

Check out Strand Consult’s library on internet regulation and contact us to schedule a workshop on constructive broadband policy which helps consumers, not that which serves Big Tech.