By Eric Osiakwan

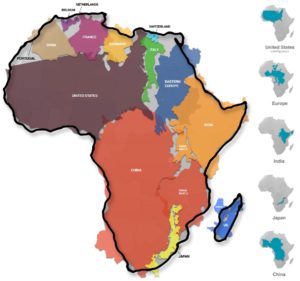

The African continent has a land area of 30.37 million square kilometers (11.7 million square miles) — large enough to fit in the U.S., China, India, Japan, Mexico, and many European nations, combined.[1] Which begs the question “how do you scaleup on a continent so big, yet so fragmented into 54 individual countries that have different laws, policies and systems of governance? Anecdotally,

RELATED: Africa needs integrated digital strategies to make AfCFTA work, says Eric Osiakwan

Africa had different kingdoms, languages, cultures ruled by chiefs and kings[2] before the scramble for the continent in 1884-5 which arbitrarily drew up borders with little regard for the pre-existing cultural and political landscape.[3] Post-colonial leaders like Kwame Nkrumah envisioned a united Africa – with a single political system and a common market that allowed for free movement of people and trade in goods and services.[4]

Sixty years after independence of most African countries, Nkrumah’s vision of a common market is coming to fruition with the establishment of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). This is one of the Africa’s Union (AU) Flagship Projects of Agenda 2063 – Africa’s development framework which is rooted in the ideals of the founding fathers of the Organisation of Africa’s Unity (OAU), the predecessor to the AU.

The Agreement establishing the AfCFTA was signed on 21st March 2019 in Kigali, Rwanda. The AfCFTA entered into force on 30th May and the operational instruments governing trade under the AfCFTA regime were launched in Niamey, Niger in July 2019. Ghana setup the official AfCFTA secretariat in Accra in 2020 and commenced trading on 1st January 2021.[5]

This unleashed the first tail wind for scaling up in Africa by reducing the political and artificial trade barriers created by the arbitrary borders, making way for a common market to trade in goods and services. The eventual free movement of people and trading in goods and services makes for a big enough market among African countries.

It is estimated that the common market created by AfCFTA is currently at about $3.4T in combined Gross Domestic Product (GDP) with a population of 1.3B people.[6] This is projected to grow to 1.7B people with $6.7T in consumer and business spending by 2030. It is estimated that by 2050, Africa would be home to 2.5B people with a combined business and consumer spending of about $16.12T.[7]

This common market will make multi-national African business ubiquitous -beyond a handful of companies dominating the telecom and tech industry. MTN – a pan-African Mobile Network Operator scaled it operations from South Africa into the rest of Africa long before AfCFTA was a thing – they proved that it could be done without AfCFTA so with AfCFTA, more African businesses can become multi-national African conglomerates.

The emerging middle-class across Africa is the second tail wind. In 2010, around 326M people or 34.3% of Africa’s population were in the middle class, a threefold increase from 1980. In Deloitte on Africa: The Rise and Rise of African Middle Class, it is estimated that the middle-class population in Africa could increase to 1.1B (42% of total population) by 2060.[8]

The African Development Bank (AfDB) has defined the middle class as the share of the population that can afford to spend between $2 and $20 per day. However, the middle class is not a homogeneous group. By the bank’s definition, Africa’s middle-class encompasses three distinct categories: the floating class living on $2-$4 per day, the lower middle-class living on $4-$10 per day, and the upper middle-class on $10-$20 per day. Investor and philanthropist George Soros has described Africa’s middle class as “one of the few bright spots on the gloomy global economic horizon”.[9]

The third and most powerful of these tail winds is the youthful population of Africa. Whilst the global north is aging, Africa is increasingly becoming youthful with an average age of 17 years making up about 70% of the population. Majority of this youth are going to constitute the global workforce and a subset of them are entrepreneurs focused on digital innovation. Over the last decade these digital entrepreneurs have unleashed a wave of innovations that solve critical societal problems.

These digital innovations are creating the digital economy in leading African markets like Kenya, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa – I christened them the KINGS countries which are leading the emergence of the digital economy in Africa.

Today, a lot of African countries have latched on to the digital economy. These digital entrepreneurs are innovating using mobile web technology to build incredible businesses in financial services (Fintech), educational services (Edtech), health services (Healthtech), Agriculture services (Agtech) and with Climate, we have Cleantech.

Some of these digital entrepreneurial ventures have become market leaders in their countries of operation with an aspiration to be pan-African, but they lack the expertise and experience to scaleup their ventures into new African markets. To ride these tail winds to scaleup their tech ventures in Africa, they need a combination of Capital, Capacity and Community to succeed – this is the focus of my next essay.

[1] https://www.visualcapitalist.com/map-true-size-of-africa/

[2] https://www.catalystplanet.com/travel-and-social-action-stories/africas-history-before-colonialism

[3] https://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/library/library_exhibitions/schoolresources/exploration/scramble_for_africa

[4] https://artsandculture.google.com/story/2gVxkcFMw9clvA

[5] https://au.int/en/african-continental-free-trade-area

[6] https://www.un.org/osaa/sites/www.un.org.osaa/files/ads2023_policy_brief_2.pdf

[7] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Friends_of_the_Africa_Continental_Free_Trade_Area_2023.pdf

[8] https://sabc.ch/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Deloitte-study-May20131.pdf

[9] https://www.uhy.com/the-worlds-fastest-growing-middle-class/