By Abdul-Hakeem Ajijola and Nate D.F. Allen

(Image: Pixabay)

Millions of internet addresses were misappropriated from the African Network Information Centre, AFRINIC, the African non-profit responsible for managing the continent’s internet registry, in a still unfolding investigation. A former AFRINIC executive was dismissed from his position after an investigation found that companies linked to the executive were selling access to AFRINIC addresses for personal profit. AFRINIC was subsequently the subject of a multimillion dollar lawsuit brought by a Hong Kong-owned firm that had acquired 6.9 million addresses, valued at $150 million, representing 5 percent of all African IP4 addresses. The case challenges AFRINIC’s authority to require its members to use African-designated addresses in Africa only—the very reason for its existence.

“Africa faces a growing array of cyber threats from espionage, critical infrastructure sabotage, combat innovation, and organized crime.”

The lack of a functioning agency to do something as fundamental as ensuring that Africa’s IP addresses remain in African hands is a direct threat to the continent’s internet access, freedom, and information sovereignty. Unfortunately, the vulnerability of AFRINIC’s IP addresses is not an isolated event but rather indicative of a broader tendency of African leaders to downplay cyber threats—at considerable cost to the continent’s economic and national security.

Africa faces a growing array of cyber threats from espionage, critical infrastructure sabotage, combat innovation, and organized crime. Still, most African countries have yet to devise a national cybersecurity strategy. Many countries with strategies fail to achieve meaningful impact because their plans are missing fundamental components, do not include key stakeholders, and are not adapted to an evolving threat landscape.

Missing Strategies

At the regional level, there is no dearth of initiatives that aim to address the continent’s growing cyber-related threats and challenges. Beginning in 2019, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Commission, in partnership with the European Union (EU), initiated the West African Response on Cybersecurity and Fight against Cybercrime (OCWAR-C) and adopted a Regional Cybersecurity and Cybercrime Strategy. The African Union Mechanism for Police Cooperation (AFRIPOL) created a Cybercrime Strategy 2020-2024 that seeks to enhance coordination, develop specialized police capacities, and harmonize legal and regulatory frameworks. Meanwhile, the African Union (AU) is working to craft and implement its own continental cybersecurity strategy through its recently established Cyber Security Experts Group. Through the formation of the Africa Cyber Experts (ACE) Community, the AU is partnering with the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE) to support cyber capacity building.

Signing of a memorandum of understanding between ITU and ECOWAS. (Photo: ITU)

Though these regionally driven efforts to develop and implement cyber strategy are noteworthy, they will only prove effective if they catalyse broad-based national-level coordination and cooperation to address cross-border cyber-enabled organized crime, violent extremism, and malicious state-sponsored activities in cyberspace. Previous efforts to improve cross-border cyber cooperation in Africa, most notably the AU-sponsored Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (the Malabo Convention), have fallen short precisely because they have failed to achieve adequate national-level support. To do so requires, as a starting point, coherent national-level cybersecurity strategies and policies.

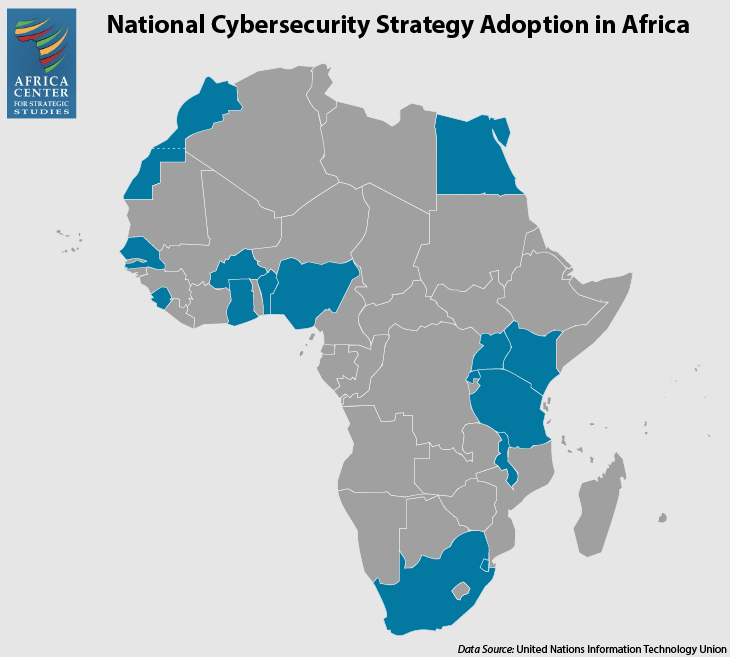

Unfortunately, progress in devising and implementing national-level cybersecurity strategy in Africa has been limited. According to the most recent data compiled by the United Nations’ International Telecommunication Union (ITU), about a third (17) of Africa’s 54 countries have completed a national cybersecurity strategy, which is less than half the global average. Governments are the single most important actor when it comes to managing cyber threats. Without national strategies, governments often find themselves unable to articulate the scope and scale of the threats they face, set priorities, marshal resources, or coordinate responses effectively across government, with the private sector, and with community-based actors.

Missing Ingredients

The mere existence of national or regional cyber strategies is not sufficient. What matters most is their design, implementation, and impact. There are a variety of good practices in both cyber and national security strategy making. At a minimum, effective cyber strategies justify why they are necessary, what to do, when to do it by, who is responsible, and how they are to be funded and implemented.

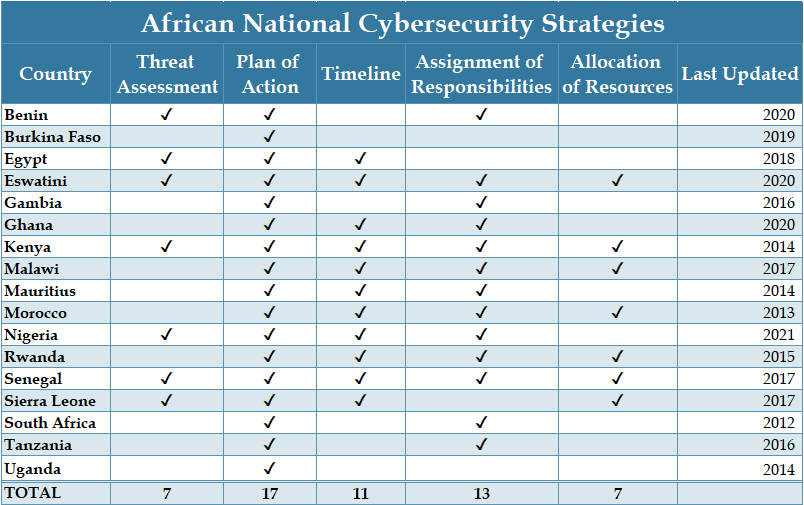

Unfortunately, in our estimation, the national cybersecurity strategies of only three African countries—Eswatini, Kenya and Senegal—possess the minimum essential criteria. These include:

- a threat assessment that identifies the scope and scale of a country’s cyber threats

- a plan of action that contains concrete goals and activities intended to address the threats

- a timeline

- an assignment of responsibilities across key stakeholders

- clear provisions that allocate resources

Fewer than half of all countries with national cybersecurity strategies possessed either threat assessments (which help justify the strategy’s existence and tailor the response to the threat) or resource allocations (which are necessary to ensure a strategy’s implementation).

Nigeria’s Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy (NCPS) development and implementation process illustrate just how essential each element is. The NCPS was developed by a broad spectrum of stakeholders representing the public sector, private sector, academic experts, civil society, and media organizations. In many ways it is exemplary—containing a threat assessment, a plan of action, a timeline for implementation, and assignment of responsibilities. Unfortunately, partly due to a lack of coordinated budget allocations across key sectors, the NCPS has not been supported with the timely establishment of its primary governance mechanism, the National Cybersecurity Coordination Centre.

Fostering Collaboration

One of the most common problems with security-oriented strategies across Africa is that they are not sufficiently inclusive. The national security establishment by function, training, and doctrine tends to err on the side of collecting and classifying information rather than sharing it. In cybersecurity, however, broad-based trust, transparency, and the sharing of threat information is crucial so that all actors, be they governments, the security sector, private sector organizations, or civil society groups, can detect and address the latest threats. To achieve maximum impact, contributions from a society-wide spectrum of stakeholders are needed in the design, drafting, and implementation of national cybersecurity strategies.

(Photo: UNESCO Africa)

The logic for including private sector actors and making public-private partnerships a focal point of national cybersecurity strategies is straightforward. The private sector possesses human capital, infrastructure, capabilities, and expertise in cybersecurity that governments lack. The financial, telecom, and technology sectors possess particularly valuable cyber capabilities. For example, because the African financial sector is a primary target for cyber fraud, Africa-based banks invest significant resources in complying with international cybersecurity norms, regulations, and standards. Their cooperation with governments, who can play a helpful role by identifying the most sensitive sectors and assisting with incident response and recovery, is essential to protecting critical national infrastructure.

The need to include and consult civil society in national cybersecurity strategy and policy is no less compelling. Civil society plays a crucial role in helping ensure that national cybersecurity strategies are widely read, popularly supported, and hold the government, private sector, and other actors accountable for misconduct. During the development of the NCPS, independent professional bodies like the Nigeria Computer Society and the Cyber Security Experts Association of Nigeria provided feedback. These groups, whose memberships cut across public, private, and nonprofit sectors and included additional stakeholders from Nigeria’s diaspora, improved the strategy due to their technical expertise, independence, and civic mindedness.

Strategies are key instruments that designate society-wide roles and responsibilities, in part to overcome obstacles to interagency coordination. Because cybersecurity is a society-wide concern with government-wide responsibilities, it can often be supremely challenging to ensure alignment across sectors. Military services hesitate to take instruction from civilian ministries. Civilian actors, likewise, are reluctant to work under military direction. This dynamic means that the most appropriate coordinating entity is often an independent cybersecurity authority directly answerable to the office of the chief of state.

“In cybersecurity, broad-based trust, transparency, and the sharing of threat information is crucial.”

The NCPS illustrates the central, but not predominant, role that security sector actors should play to ensure inclusive design and implementation. The strategy development process was led by the Office of the National Security Advisor, who reported directly to President Muhammadu Buhari. The Secretariat charged with coordinating the process was made up of national security actors and academics. The members of the committee charged with designing and drafting the strategy, however, included a much broader range of stakeholders drawn from the private sector, civil society, civilian line ministries, and independent experts. Early in the design process, each of these stakeholders, as well as external ones, were given numerous opportunities to voice their views both orally and in writing. Soliciting a range of views early enabled the drafting, validation, and dissemination of the strategy to proceed quickly and with limited opposition.

This inclusive process also ensured a broad recognition, even among security actors, of the importance of citizen-centric cybersecurity policies. As observed by Nigeria’s National Security Adviser, General (ret.) Babagana Monguno, “Nigeria’s cyberspace has become a centre stage for governance, new business innovations, communications and social interactions. This trend has created an opportunity for us to redefine our national objectives and address some of the major developmental challenges currently facing the country.”

Finally, the end product has as important a role in ensuring inclusivity as the process. The intended outcome of a strategy is that it is implemented in the best interest of stakeholders. Stakeholders must not only feel involved, but the document itself needs to be short and direct to ensure that it is widely read. Policy documents are often written by and targeted for senior policymakers rather than the mid-level public servants charged with implementing them or the nonexperts they intend to benefit. Particularly in a political, cultural, class, demographic, religious, and ethnic context as diverse as those faced by most African countries, policymakers would benefit from writing shorter, simpler cybersecurity policy documents, devoid of overly technical jargon, intended for as broad an audience as possible.

Adapting to an Evolving Threat Landscape

AU Cybersecurity Experts (Photo: AU).

Once in place, many countries fail to put mechanisms in place to enable their cybersecurity strategies to be proactive and adaptive to the rapidly evolving cyber threat landscape. Ironically, the five African countries that have not updated their national cybersecurity strategies in the past 5 years—Kenya, Mauritius, Morocco, South Africa, and Uganda—are widely considered to be among the continent’s most cyber mature. Without updated strategies, however, they are likely to fail to anticipate, respond, and adapt to the latest threats. To ensure continued relevance, national cybersecurity strategies should ideally be updated every 5 years as a matter of course. A central challenge for African legislatures, then, is to enact laws that empower regulators to quickly adapt in a dynamic environment without trying to legislate minutia.

It is similarly important that national cybersecurity strategies and policies be forward looking. Insofar as they do contain threat assessments, virtually all of Africa’s existing national cybersecurity strategies diagnose the contemporary cyber threat landscape rather than proactively think about likely future trends and threats. As a result, most African nations are woefully underprepared to confront advances in artificial intelligence, wireless communications, quantum computing, and automation that are likely to characterize the coming decade. African states will not be able to optimally leverage these technologies to their benefit if they are not prepared to confront the threats and challenges.

Humans at the Center of the Machine

All African governments, regardless of their level of cyber maturity, could benefit from an improved national cybersecurity strategy. Less cyber-mature countries should focus on getting a basic strategy in place with all the necessary elements. In some cases, they may need to start with basic cyber capacity building to establish a lead authority or cyber emergency response team that can serve as a focal point to ensure national cybersecurity strategies reflect technical realities and good practices.

“To ensure continued relevance, national cybersecurity strategies should ideally be updated every 5 years.”

More cyber-mature countries should focus on overcoming obstacles to interagency coordination, regularly updating their strategies, and attempting to look ahead to meet the next generation of threats. They can and should play a leading role in establishing good practices, building capacity, supporting indigenous research and development of digital tools (including algorithms and encryption technologies), and improving regional and international cyber cooperation in Africa.

At the continental level, mechanisms are needed not only to improve coordination and cooperation across states and regional organizations, but also to facilitate resource sharing. There are many African-led initiatives that, if scaled up, would significantly and cost-effectively improve continental cyber capacity, coordination, and ability to deal with shared threats. These include the Policy and Regulation Initiative for Digital Africa (PRIDA), the West African Response on Cybersecurity and Fight against Cybercrime (OCWAR-C), the AU Commission’s-Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE) joint cyber capacity building initiatives, and efforts by the Africa Computer Emergency Response Team (AfricaCERT) to establish and improve coordination among cyber emergency response teams across the globe. Outside actors who wish to support cyber capacity building efforts in Africa should first seek to partner or support these and other worthy initiatives before undertaking efforts on a bilateral or unilateral basis.

(Image: Pxhere)

African governments, national security actors, the private sector, academia, and civil society must appreciate that the decisions they make now will determine cybersecurity strategy, policy, and culture for the generations that follow. Those charged with the responsibility of drafting cyber strategies in Africa should never forget for whom, ultimately, the strategy is developed: people (from itinerant farmers to military officers) who are becoming increasingly reliant on digital services and who are vulnerable to digitally based threats.

Future generations will judge African leaders not solely on how effectively they respond to cybersecurity threats, but also on whether their cybersecurity strategies reinforce the social contract between governments and citizens.

Abdul-Hakeem Ajijola is the Chair, African Union Cyber Security Expert Group (AUCSEG), Addis Ababa.

Nate D.F. Allen is an Assistant Professor for Security Studies for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Additional Resources

- Nathaniel Allen and Catherine Lena Kelly, “Deluge of Digital Repression Threatens African Security,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 4, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Cyberspace Security Priorities for Africa’s National Security Actors: Executive Summary,” Virtual Academic Program, August 3–25, 2021.

- International Telecommunication Union, National Cybersecurity Strategies Repository.

- Abdul-Hakeem Ajijola, “Addressing the Flaws in “Africa’s” Policy Development Process,” May 5, 2021.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria, National Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy, February 2021.

- Nathaniel Allen, “Africa’s Evolving Cyber Threats,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 19, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “National Security Strategy Development in Africa: Toolkit for Drafting and Consultation,” January 2021.

- Luka Kuol and Joel Amegboh, “Rethinking National Security Strategies in Africa,” International Relations and Diplomacy 9, no. 1 (2021).

- Claudia Soares de Almeida, “A Problemática da Cibersegurança: o Caso da Estratégia Nacional de Segurança no Ciberespaço,”IDN Cadernos 30, Instituto da Defesa Nacional, September 2018.

- International Telecommunication Union, et al., Guide to Developing a National Cybersecurity Strategy y: Strategic engagement in cybersecurity, 2018.

First published by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies